When our campus last searched for a new Chancellor, we said that we need a person with the potential to become a leading public figure in the region. In order to serve not just the regional public university but the region, we need this to be true.

A new @InsideHigherEd article breaks the work of a chancellor out into four roles. Chief storyteller, chief spokesperson, chief recruiter, chief thought leader.

I imagine a carefully nurtured ecology which supports any new leader’s growth in the new contexts of the job leading a regional public university.

- Intentionally cultivating in the leader knowledge and ideas not just about higher education but also about the resources and challenges of this historical moment in the region (and yes, the nation, the world). Being taught that, in part, by the people of the region.

- Out of this fertile soil, intentionally cultivating the stories needed to interest and move both campus and community.

- Upon that base, now being equipped not just to recruit students to apply but also intentionally and strategically to recruit the region’s leaders and citizens to engage with the campus (and to support it), to recruit faculty not just to their listed duties but to engage with the region’s challenges in this historical moment.

- And in this process, the Chancellor almost inevitably becoming a leading public figure in the region.

Here is the Inside Higher Ed article by Bill Faust that breaks out the elements of the Chancellor’s role.

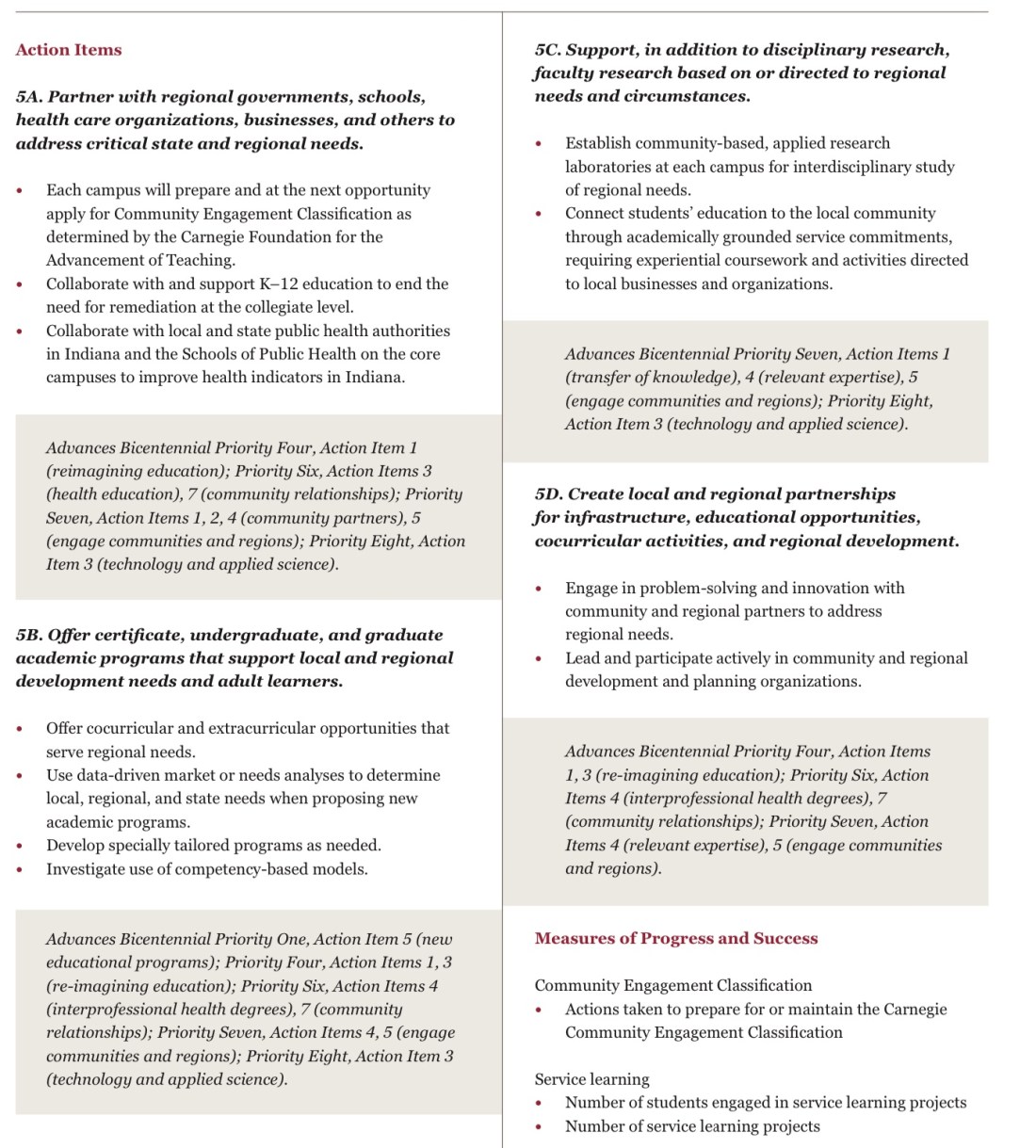

And here, an example of structures of community and campus engagement that might have a chance to grow as a result. From IU’s Blueprint 2.0, see interlocking items 5.B, 5.C, and 5.D: